Head Trauma Strongly Linked To Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy But Precise Relationship Not Yet Known

No need to panic

“The last thing we want is for people to panic. Just because you’ve had a concussion does not mean your brain will age more quickly or you’ll get Alzheimer’s,” says Steven Broglio of Michigan NeuroSport and Director of the NeuroSport Research Laboratory at the University of Michigan, and the author of the 2012 study suggesting that concussions may speed up the brain’s natural aging process. (27)

Broglio stressed that the influence of various lifestyle and environmental factors, such as smoking, alcohol consumption, physical exercise, family history (genetics), whether or not a concussed athlete “exercises” their brain, and even how dense is the gray matter in a person’s brain, which gives them greater “cognitive reserve” to draw upon ,may also impact the brain’s aging process, and that “concussion may only be one small factor.”

In addition, he said, like many other scientists, he is quick to acknowledge that this line of research is still in its infancy. “‘It’s not entirely clear,” Broglio told the Kalamazoo News, “if and how the brains of young athletes are affected by the sports they play. ‘We are realizing it’s probably not how many concussions you have that makes a difference, but the total exposure’ to concussive and sub-concussive blows.”

“What we don’t know is if you had a single concussion in high school, does that mean you will get dementia at age 50?” Broglio said. “Clinically, we don’t see that. What we think is it will be a dose response.”

“So, if you played soccer and sustained some head impacts and maybe one concussion, then you may have a little risk. If you went on and played in college and took more head balls and sustained two more concussions, you’re probably at a little bigger risk. Then if you play professionally for a few years, and take more hits to the head, you increase the risk even more. We believe it’s a cumulative effect.”

Does the average high school athlete face risks similar to those of former professional football players – such as those whose brains, upon examination after death, show signs of CTE or who, even if still alive, exhibit signs of serious depression or early-onset dementia which researchers have linked to their years on the playing field? Broglio says that there is little to no evidence that they do. “We’re not seeing an epidemic of men in their early 50’s with early Alzheimer’s because they played high school football,” Broglio told a Michigan newspaper in commenting on his 2012 study. His observation is supported by the 2012 study (33) by Mayo Clinic researchers, which found no increased risk of neurodegenerative disease in men in their 60’s and 70’s who played high school football in the 1940’s and 1950’s.

Boston University’s Cantu has also been, at times, a voice counseling restraint. “For my patients who’ve had multiple concussions and fear that they are at risk for developing CTE later in life, I offer simple advice: Relax. The connection has been greatly overstated.” (44)

The authors of a 2015 editorial in the British Journal of Medicine (67) agreed: “While cases continue to surface and receive tremendous media attention, the fact remains that current evidence suggests that the risk is very low when we consider the total number of athletes who have played American football.”

Dr. Cantu’s colleague, Dr. Robert Stern, told the CBS newsmagazine, Sixty Minutes, the same thing: [J]ust because you hit your head a bunch, doesn’t mean you’ll get the disease,” says Stern, who made it clear to the program’s Steve Kroft “that most NFL players don’t,” and that the number of confirmed cases is still small, with thousands of former NFL players seemingly unaffected. (70)

Prevention and treatment

The simplest way, say most experts, to decrease the risk of CTE, whatever it is, is by

- limiting exposure to trauma by reducing helmet-to-helmet contact in football through the teaching of proper tackling technique;

- limiting exposure to trauma through rule changes and better rules enforcement (such as by penalizing intentional hits to the head, as is happening in football and, to a lesser extent, in ice hockey);

- limiting exposure to impacts that may result in concussion or mTBI from subconcussive blows by reducing the number and length of full-contact practices. Given the potentially large number of head impacts a football athlete may experience over the course of the season and their career, some experts have suggested implementing head impact monitoring and impact limitation strategies similar to pitch counts in baseball.

- Over the last five years limits on full-contact practices have been implemented at every level of football, from the National Football League, to college football (Ivy League and Pac-12), to the high school level (46 of 50 state athletic associations now limit full-contact practices, both in the pre-season and regular season, especially since the National Federation of State High School Associations recommended such limits in November 2014), and down to the youth level (Pop Warner). All are intended to limit the amount of total brain trauma football players sustain as a result of repetitive sub-concussive hits.

- Two studies by Broglio, the first in 2013 (16) and a second published in 2016 (72), found that limiting or eliminating contact practices in high school football would result in reducing impacts over the course of a football season (regular season and playoffs), the first reporting an 18% to 40% reduction in head impacts, and the second finding that impacts to the head were reduced by 42% after implementation of a rule in Michigan reduced contact practices from 3 to 2 per week. Despite these findings, Broglio continues to caution that, until the risk factors for CTE are better defined, and research shows that reducing the time spent learning to tackle in practice will not lead to increased risk of concussions in games, policymakers should proceed with caution in imposing such limits. While recognizing that “contact sport athletes appear to be at a greater risk for developing CTE,” Broglio was careful to note the absence of studies “indicating the relationship between head impacts, concussions, and other factors (e.g. genetic profile) that may trigger the disease pathway.” Until the risk factors for developing CTE are better defined, Broglio says, the effect of limits on full-contact practices on the risk for CTE is “unknown” and strategies designed to reduce those risks will necessarily remain “an educated guess, at best. … Ultimately, a comprehensive approach that includes, but is not necessarily limited to, modifications of head impact exposure, equipment modifications, rule changes and enforcement, and changes in game culture may all be needed to reduce injury risk,” Broglio concluded.

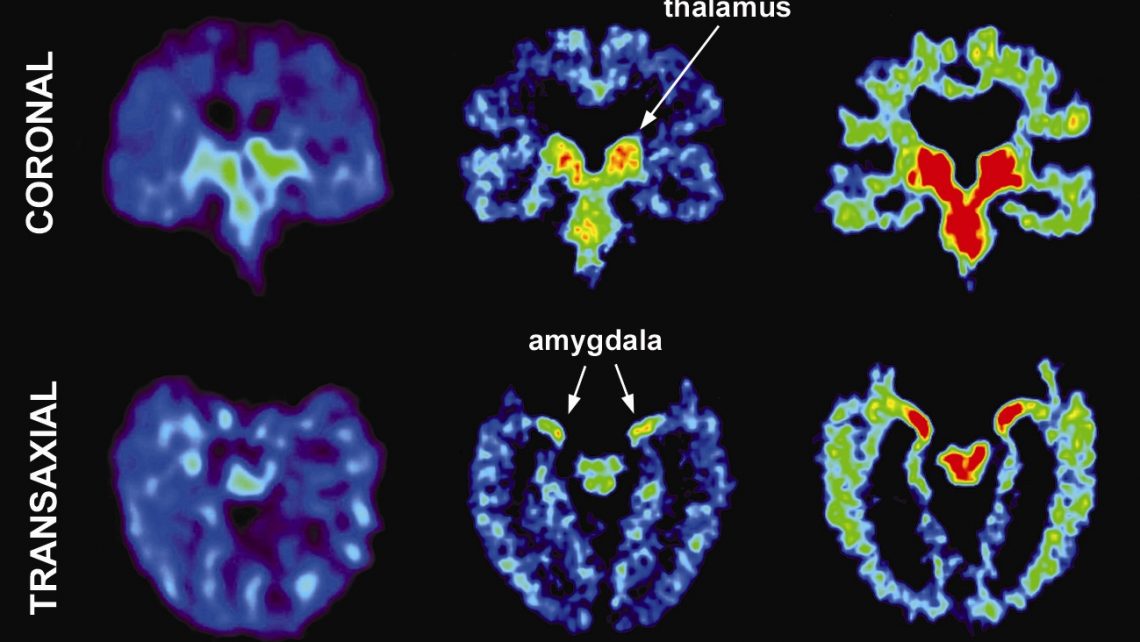

- using more conservative return-to-play guidelines: Because the absence of observable symptoms may not be a reliable guidepost (some indications of impaired brain function are not detectable except with very sophisticated brain imaging equipment), some experts propose return to play guidelines requiring at least 4 to 6 weeks before a return to contact sports to facilitate more complete recovery and to protect against re-injury, as research shows that a second concussion occurs much more frequently in the immediate period after concussion. MomsTEAM’s expert sports neuropsychologist, for instance, recommends in her 2012 book, Ahead of the Game: The Parents’ Guide to Sports Concussions, that young athletes with diagnosed concussion not return to play for at least three weeks after injury. Animal studies suggest there is an expansion of brain injury and functional recovery is slowed if the animal is subjected to overactivity within the first week (supporting the concept of cognitive rest recommended for children and adolescents);

- proper care and management of mild TBI (cognitive and physical rest in the period immediately after concussive injury, gradual return to a full academic day, e.g. “return to learn”) and following a six-step process of gradually increased exercise (without concussion symptoms returning) before return to play; and

- player and coach education.